Western Grebe

General Description

Western Grebes are large and slender with long necks and long, thin bills. Plumage is dark gray above and white below, with a clear color division. The top of the face is black, and the bottom white. The black extends below the eye in the Western Grebe. (In the closely related and similar-appearing Clark's Grebe, the black ends above the eye.) The bill of the Western Grebe is yellowish to dull olive.

Habitat

In winter Western Grebes are found mostly on saltwater bays. During the breeding season they are found on freshwater wetlands with a mix of open water and emergent vegetation. The breeding areas are located in the central arid steppe and Big Sage/Fescue zones stretching from California north and east to south-central Canada.

Behavior

Western Grebes are highly gregarious in all seasons, wintering in large flocks and nesting in colonies. The neck structure of Western Grebes allows them to thrust their beaks forward, like spears, a motion they use to catch prey. As a family, grebes are known for their elaborate courtship displays. Western Grebes and the closely related Clark's Grebes perform the most spectacular displays of the family. The displays of Western and Clark's Grebes are almost identical; the only apparent difference is that one of many calls differs in the number of notes.

Diet

In all seasons and habitats, the primary food of Western Grebes is fish.

Nesting

Together, the male and female Western Grebe build a floating nest made of heaps of plant material anchored to emergent vegetation in a shallow area of a marsh. The female lays three to four eggs, and both parents incubate. Once hatched, the young leave the nest almost immediately and ride on the backs of the parents. Both parents feed the young. Young are plain gray and white, not striped like the young of other grebes.

Migration Status

Many birds from the northern part of the population migrate at night to the Pacific Ocean.

Conservation Status

At the turn of the 20th Century, tens of thousands of Western and Clark's Grebes were killed for their feathers. With protection, they have recovered and can now be found breeding in new areas not occupied historically. Fluctuating water levels, oil spills, gill nets, and poisons such as rotenone (used to kill carp) are factors that negatively affect the population. When approached by humans, the parents will leave the nest, leaving eggs vulnerable to predation and the elements. Thus, areas frequently disturbed by humans may have low productivity.

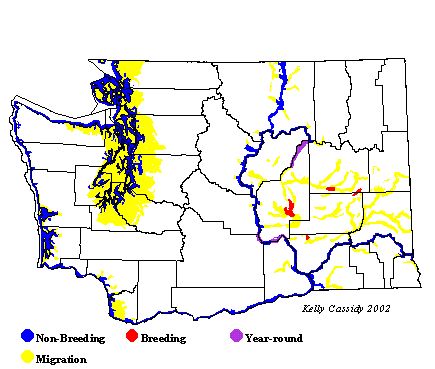

When and Where to Find in Washington

Western Grebes can be found during the breeding season on large ponds and reservoirs in the Big Sage/Fescue zones in eastern Washington, especially at Moses Lake and Potholes Reservoir in Grant County. Nesting colonies have also been found near Crab Creek, Frenchman Hills Wasteway, Lake Lenore, and many ponds in the Columbia National Wildlife Refuge, all in Grant County. In Douglas County they can be found at Banks Lake. Non-breeders can be found in the summer in coastal regions of the state as well, such as in Bellingham Bay. In winter Western Grebes are rare in eastern Washington but common on the coast and in Puget Sound. Wintering flocks with birds numbering in the thousands were historically present in Bellingham Bay. Now large numbers of Western Grebes winter at Quartermaster Harbor (Vashon-Maury Island) and Saratoga Passage. There are also a few hundred on Lake Washington and on Elliott Bay.

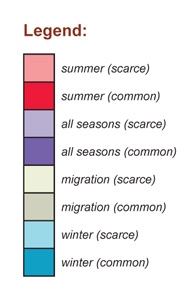

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | U | U | F | C | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | U | R | U | U | F | C | C | C |

| North Cascades | U | F | ||||||||||

| West Cascades | U | U | U | U | R | U | U | U | ||||

| East Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | F | F | U | U | U |

| Okanogan | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | F | C | U | R |

| Canadian Rockies | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | F | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | U | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map